- Home

- Kendra Fortmeyer

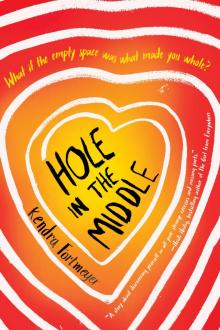

Hole in the Middle

Hole in the Middle Read online

Copyright © 2018 by Kendra Fortmeyer

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are

the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any

resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events,

or locales is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Soho Teen an imprint of

Soho Press, Inc.

853 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fortmeyer, Kendra, author.

Hole in the middle / Kendra Fortmeyer.

ISBN 978-1-61695-956-2

eISBN 978-1-61695-957-9

1. Abnormalities, Human—Fiction. 2. Interpersonal relations—Fiction.

3. Self-acceptance—Fiction. 4. Celebrities—Fiction. I. Title

PZ7.1.F667 Hol 2018 [Fic]—dc23 2018004787

Interior design by Janine Agro, Soho Press, Inc.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

for all the hole kids—

you’re not alone

1

Here are the options for a girl like me:

Option A: Not mention it on the first date, or the second or third. We get to know each other, laugh, accidentally-on-purpose brush each other’s shoulders. We go to a movie and say stupid things during the dramatic scenes, and I look over and notice that you’re crying, and you look over and notice me noticing you crying, and we both pretend not to notice that the other person is noticing these things, but you take my hand, quietly and gratefully.

A fondness begins to well. A language begins to form, a gauze-webbed network of inside jokes. We text each other and are paralyzed with terror from the moment we hit send until the phone buzzes back and our hearts start to beat again. Our friends get sick of us. The world takes on a brightness that it only does for the specially loved. I start to wonder if you are The One, and I can see, gleaming in your eyes, the kernel of the notion that I am The One, too.

At some point you want to take the next step. The Big Step. Maybe we are at your house; maybe your parents are out of town; maybe you make some dumb excuse about showing me something in your bedroom and I say something witty like “Okay,” and my heart is pounding, and I don’t know how to speak, and it’s not until you close the door behind us with a faint click that I can say,

“Um, Hypothetical Person?”

And you, running your hands down my sides hazily, fingers curling up through my blouse, murmur into my hair, “Mmm?”

“There’s something I have to tell you,” I say.

I lift up my shirt and you see it. It is egg shaped, the Hole: an imperfect oblong just to the lower right of my navel, about the size of a peach or a fist. It is perfectly smooth, sealed: a toroid tunnel of white skin. Peering through it, you can see the room behind me. You can read the titles on the bookshelf.

“Whoa,” you say.

“Yeah,” I say.

“Holy shit,” you say.

“Yep,” I say.

“Does it hurt?” you say.

“No,” I say.

“What happened?” you say.

“Nothing,” I say. “I don’t know. I was born with it.”

And this is the moment I lose you.

Option B: I tell you up front.

“I’m that semi-cute, flat-chested girl who makes fun of your groceries at the local food co-op. I bike and paint and make up nicknames for people I’ll probably never work up the nerve to talk to; I’m a nightmare only child of a nightmare single mom; also, I have a giant, hermetically sealed hole in my torso that you could stick a fist through. Seventeen, nonsmoker, INTJ.”

I don’t get many takers.

2

My best friend Caroline sprawls over the edge of my bed, upside down, pulling plastic-wrapped pastries one by one from a white paper bag. It’s barely 9 a.m., but her delicate skin is flushed from biking home in the punishing North Carolina August heat, her hair a matted blond mess of sweat and flyaways. She’s stopped back at our apartment between her morning shift at Java Jane and our class’s pre–senior year kickoff beach party. I say “our” because it’s our senior year, not our party. Very few things are my party. Social-gatherings-of-everyone-I’ve-known-since-prepubescence-and-am-a-mere-180-days-away-from-escaping-forever are indubitably not my party.

“It’s not too late for you to come, you know,” Caro says. “We could sneak you onto the bus. Emmeline’s dad does construction—we’ll build a wooden horse, Odysseus-style. Or tie you to the bottom of a sheep.”

“Or just tie me to Emmeline.”

Caro eyes me.

“Because she’s a sheep.”

Caro sticks her tongue out at me, upside down. Her mother tried for years to push her into gymnastics, trapeze, space camp, but Caro wasn’t interested. “I don’t want to make being upside down a job,” she said at age nine, dangling from the sofa with her hands on her chubby hips. “I just like the way it makes my face feel.”

I love 387 million things about Caro, including this, but it is still not compelling enough for me to spend all day on a school-sponsored beach trip, hunched in a huge T-shirt while people I had pre-algebra with cavort half-naked in the water.

Caro sighs and stops unpacking pastries.

“I wish you were coming,” she says. “It’s only eight hours, and I want you to hang out with me. Me, your best friend, Caroline, who you love the most.”

“I do love you the most, but that is still eight more hours than it’s physically possible to have fun at a beach.” I flop on the bed beside her, letting my head dangle toward the unvacuumed carpet. “This is a principle upon which my universe operates, Caro. Therefore, in the unlikely chance I did have fun, I would explode out of sheer cognitive dissonance.” She opens her mouth, and I say, “Besides, Todd’s coming. I don’t want to be a third wheel.”

“You’re never a third wheel,” Caro protests. “Todd loves you.”

I love 387 million and one things about Caro, including this: she genuinely believes nice and absurd things.

We survey my upside-down bedroom in silence: the hamburger-shaped beanbag chair, the sketches taped up amid the art prints I scrounged from Goodwill, the precarious tower of cereal bowls in the corner. Deep in my body, my quiet spine uncurls.

“What if,” Caro says, “you came and spontaneously combusted from fun but timed it with the music so that it was the most epic beat drop of all time?”

“Tempting,” I muse. “But I’d probably still somehow end up with sand in my butt crack, so pass.”

Caro begins sorting the day-old pastries onto our stomachs by feel: three muffins, a broken cookie, a pile of unloved scones. “Morgs, you won’t third-wheel forever,” she says. “There’s someone out there who’s a perfect match for you.”

“How hard did you hit your head just now? You know, when you fell off topic?”

She ignores me. “I’m just saying. A little optimism never killed anybody.”

I don’t respond. One of the awkward things about being permasingle is how it makes other people feel bad for you. I mean, sure. Sometimes when I go the long way around to avoid the make-out stairwell at school, or when I see happy couples on billboards advertising Mentos or whatever, I get this little aching twinge, sneeze-quick. The word oh. Just that. As in, Oh, wouldn’t it be nice. But it usually fades pretty fast. The thing is, I like me. I’ve been me my whole life,

and I’m going to keep on doing it. So why not?

Caro’s phone chimes and she spills herself upward, hair and crumbs curling onto my duvet. “Okay, Miss Too-Cool-for-Back-to-School,” she says brightly. “How about this: YYS is playing an anti–back-to-school party tonight off Gorman Street. Morgs, this is perfect! Come to this. You have to come to this. I promise, it won’t be any fun at all.”

I groan. Yum Yum Situation is a local college band. Specifically, Caro’s extremely boring boyfriend Todd’s local college band. They’re NC State students who specialize in power pop songs with atonal bass lines and tortured, insightful lyrics like, “It’s not the size of the boat, it’s the motion of the—oh-oh!” Every other week they play some hipster house party, and every other week I end up in a corner with somebody’s drunk girlfriend telling me how much she loves her drunk boyfriend, and counting the minutes until I can go home.

“You know what my kind of party is?” I ask, hopefully. “The staying-at-home kind of party.”

Caro snorts and bumps me with her hip. A muffin rolls off of her stomach and slides into the well where my black T-shirt stretches taut over the Hole.

“Dear Morgs, kindly come to this party because you’re getting that glassy, I-haven’t-interacted-with-humans-in-three-days look in your eye. Love, Caroline.”

“Dear Caroline,” I say, “I’ve interacted with, like, four humans already today.”

“PS: not counting me.”

“Three humans.”

“Not counting your mother calling to yell at you about getting your shit together.”

“In my defense,” I say, “she counts as at least sixteen people.”

Caro checks her watch. “I’ve got to go. I promised Angela I’d sit with her on the bus.” She points to my forehead. “Party. Think about it.”

“Thinking,” I say. “Bye.”

I lie on the bed for a long time after the door clicks shut, ears ringing in the sudden hush. Our empty apartment smells of turpentine, hollow and gray. Outside, the traffic sounds of Hillsborough Street thrum through the August afternoon like the pulse of the life I’m not quite living.

I push myself upright, brushing away crumbs. It may be two days before senior year, and everyone else is loading up on school supplies and wondering if their crush will notice them this year and saying to one another, We’re seniors, I can’t believe we’re finally seniors, but there are some principles upon which my physical universe operates, and here is another: while everyone goes to the beach, I drive to the medical clinic, alone, so the people paid to care can verify that I haven’t collapsed.

For an introvert, my social calendar is actually packed. See: Liaisons with old men in lab coats. Hot dates with cold exam tables. I have a pulmonologist, a cardiologist, a dermatologist, a rad feminist gynecologist, a renal specialist, a radiologist, a phlebotomist, a chiropractor and a host of wisecracking x-ray technicians, not to mention a general practitioner.

The Hole is nestled below and to the right of my navel. Its lip is soft and rubbery, lined with smooth, hairless flesh, and my organs have shifted neatly up and down and to the left, rearranged around the absence at my core. We tried for years to make me whole. The records live in a hushed drawer in one of Mother’s offices, eighteen separate counts of failure and disappointment. The doctors took grafts from my buttocks, from Mother’s, from anonymous donors who, I realized upon passing my driving test at sixteen and ticking the organ donor box, had probably died on highways, whole and healthy blood gushing out onto distant asphalt. But each time the implanted flesh shrank from mine, drawing thin and translucent around the edges. I found dead transplants shriveled in my bed sheets; they dropped with flaccid glops to the floor of the shower, quivering like jellyfish on the drain. About a year or so ago, Mother threw up her hands. Something something wait until technology something adolescence something. Which, to be honest, is fine with me. Have you ever been sick? Like, really sick? Like, long-term, mysterious, nobody-can-tell-you-why-or-how-you-might-get-better-or-if-that’s-even-a-possibility sick?

If you haven’t, I’ll tell you, it’s like this:

Imagine you’re balancing on a tightrope. Tugging on one of your hands, threatening to knock you off-balance and into the abyss, is hope.

Tugging your other hand is despair.

Waiting at the other end of the tightrope is the semblance of a normal life.

You have to get up every morning and walk that tightrope, end to end. You might have doctors shouting, “We found a new omega-17 vitamin that accelerated discrete tissue growth in fruit flies, and we think it could cure your . . .” and you might have a little kid in the grocery store point at you and ask loudly, “Mommy, what’s wrong with that girl?” and if you give in to any of them, if you listen for even half a second, you’ll fall straight down into hopelessness or heartbreaking hope, and it could take you a week to get up again.

The only way to make it to the end of every day is to give zero fucks.

Which is good, because I’m seventeen, and I’ve just about run out.

These days, I’m mostly in maintenance mode, visiting with my doctors on the reg so Mother can check make sure daughter isn’t dying off the to-do list. My posture could be better, and I think I’m missing a few minor abdominal muscles, but beyond the surgeries, I’ve led a weirdly healthy life: no broken bones, no cavities, no stints in an iron lung. The worst thing that’s happened to me health-wise was the time I contracted chicken pox and couldn’t find a way to scratch the bit between my descending colon and my small intestine in polite society.

I’ve been with my primary doctor, Dr. Takahashi, for nearly ten years. He’s a small man in his fifties, with salt-and-pepper hair and fine cheekbones warped round by his enormous glasses. We’ve been through everything together: I’ve cried about bad grades on this examination table, brought him drawings. He patiently gave me the facts when I was eleven and thought the fat little lumps of my breasts were cancer. He lost sleep when I hit a growth spurt at thirteen that we feared would stretch the Hole out to expose my spine, dissolving me into a human stew of raw nerves and vertebrae. He’s the only one I trust to touch the Hole—not my other doctors, not Caro, not even Mother since I was six and began to bathe by myself.

Even so, there’s a barrier between us. He’s always washing his hands, donning gloves, never letting me in on his true thoughts or feelings. I sometimes want to say, “You know more about me than 99.9 percent of my classmates; can’t we just hang out?” But I guess that’s not the point.

“How’s it going today, Morgan?” Taka asks as he washes his hands. I turn away, the spatter of the water in the sink grating on my nerves. I know it’s standard practice, but come on, it’s not like you can catch Hole. Although I like this idea: Dr. Takahashi starting awake in the night next to some shadowy-faced wife, lifting his hands from his bedspread and seeing . . . no! No! The beginnings of little pits, burrowing through his skin like worms! Holding them up to the moonlit window and seeing through them like lace! A swelling of music. And then, black screen: THE HOLE. Coming to theaters in October.

“What?” I ask.

“I said, has your menstrual cycle evened out?”

“It’s okay,” I say. “It was kind of weird for a while.”

Taka’s eyes flicker over the screen, through electronic charts and notes. “You said it had been sporadic.”

I normally menstruate once every two months. Something about the way my internal organs have rearranged to accommodate the Hole. Things aren’t quite where they should be. My life lacks normal flow.

“Oh, yeah,” I say. “For a while I was on this new brand of tampons. I think they dried me out.”

Dr. Takahashi doesn’t blink. Nor, to his credit, does he acknowledge this obvious bullshit. “Have you thought about going on birth control?” he asks.

I watch him as he prepares a needle for a blood draw. I�

�ve never had the luxury of being afraid of needles. Me being afraid of needles would be like a drowning person being afraid of the lifeboat.

“Please,” I say, as my blood beads darkly in the syringe. “Like I’m ever going to need it.”

Because Caro is right, I am categorically terrible at meeting people. Call it self-preservation, call it being antisocial; call it whatever you like. If I had my way, no one would get close enough to know my name, let alone learn that I’ve got a great big unholey secret. My report cards from kindergarten: good vocabulary, mediocre penmanship, DOES NOT PLAY WELL WITH OTHERS.

I thought things would change every year—that I would finally find my super-close, college-brochure-diverse, Girls-esque group of friends who I would share clothes with and pee in front of. People who would finally make me feel at home. But except for Caro, somehow I’ve always remained awkwardly on the periphery. It’s like normal life is a code I never quite learned how to crack. I grew up around doctors, around Mother, in expensive clinics and on- and off-set—in and out of school, obsessing over x-rays, gulping down pills and hopping on one rattling bandwagon of miracle cures after another, while other kids my age watched anime and worried about whether they could actually get cooties from their gym lockers. Even with a decade of sweet, weirdly anomalous Caro telling me otherwise, it feels too late to catch up.

I’m pulling out of the parking lot of Taka’s clinic when my phone jumps in my lap. I fumble with my earpiece and hit accept. “Hello?”

There’s an awkward pause. I try again. “Hel—”

“Would you buy a fragrance called Lambence?”

I frown at the road, hearing now the vague moth-wing static of overseas air. “Isn’t that a kind of eel?”

“That’s what I told Srivani,” my mother mutters. “That idiot.”

“Mother,” I ask, calmly, “why are you naming fragrances?”

“Christine wants me to launch a limited spa line for Christmas.” She sighs. “Ayogatherapy. Like aromatherapy. It’s ‘clever.’ How are your college applications coming? Did you look at the brochures Tabitha sent you?”

Hole in the Middle

Hole in the Middle